Unofficial bio

Editor’s Note: This statement is not an official band statement or anything of the sort. It was written by a fan and is in some way sentimental and thus utterly biased. But we think it touches most of the bases – lets you know where they’ve been and where they’re going.

Soulhat is virtually a Texas institution. And much like one of the most famous and talented of Texas’ native sons, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Soulhat got their start in the steamy, crowded clubs of Austin, the Live Music Capital of the World.

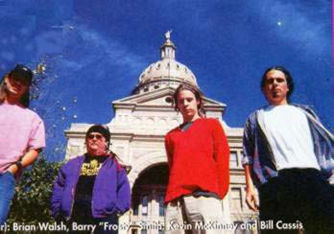

Back in the Summer of 1990, Kevin McKinney and Bill Cassis were friends and fraternity brothers at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas (Kevin was a student; Bill left in 1989). Like many students in that once quaint town, McKinney made weekly pilgrimages to Austin (Cassis was already living there), soaking up the local music scene but dreaming of something in which they could be involved. The two were well known at Southwestern as musicians, though neither had steady gigs at that point. Kevin had been playing bass in cover bands: Bill was playing guitar with E.R. Shorts.

Though playing on campus got them some social exposure, their break came from a SXSW “Battle of the Bands,” that same year. Shortly after backing-up local music hero E.R. shorts & helping him win top honors at the Battle, Bill & Kevin decided to form their own band with Brian Walsh (another S.U. grad) on bass.

Though playing on campus got them some social exposure, their break came from a SXSW “Battle of the Bands,” that same year. Shortly after backing-up local music hero E.R. shorts & helping him win top honors at the Battle, Bill & Kevin decided to form their own band with Brian Walsh (another S.U. grad) on bass.

Walsh was already playing guitar in Beware of Maya (BOM), among other groups. He’d been around the Austin music scene a bit longer, yet seizing the opportunity to perform in a new project, Brian gave these younger fellows a chance. Together, they formed a band called Soulhat. The early line-up included McKinney on acoustic, rhythm guitar and vocals, Cassis on lead guitar, Brian Walsh on bass guitar, and Ian Bailey on drums.

Soulhat’s first real gigs were in a bar known only as the Club, a skinny little alley with a roof overhead; a place even more crowded than Black Cat shows would be a couple of years later. A tip jar hanging from a string was hoisted between the bar and the stage and served as the band’s only paycheck for those first shows. Yet Soulhat kept coming back because the crowds kept getting bigger, the tip jar getting ever more full.

Fueled by throngs of students and curious passers-by, the Club gigs kept growing larger until soulhat and its fans had simply outgrown the alley-like confines of the Club. After a series of shows at Austin’s infamous Black Cat Lounge, Soulhat was given a regular headlining gig, on Thursday and Saturday nights. Let me tell you, for those of you who weren’t there: those Black Cat shows were really special. The jams never seemed to end and the crowds were as strange and diverse as Austin before the current boom.

The Fans: We’d be hard-pressed to describe the self-coined ‘Hat Heads’ any better than the Austin Chronicle did during the late summer of 1991: “Clean cut and evil looking fraternity boys co-mingle with tattooed, black clad alternative rockers. Politically correct Birkenstockers dance and drink in harmony with sorority girls and skimpily dressed strippers out for a night away from clothes shedding.” That’s exactly how it was — a truly random group of folks drawn there only by their love for songs that had no boundaries, no time constraints, no label or genre. And I suppose the free hot dogs at the Black Cat didn’t hurt either!

During 1991, Soulhat added to its line-up the player who would perhaps donate the most to its distinctive sound and feel – Barry “Frosty” Smith. Smith was already internationally known for his contributions to the live grooves of some of rock’s greatest bands, having drummed with the likes of Lee Michaels, Jimi Hendrix, Parliament-Funkadelic, and Sly & the Family Stone. But somehow it didn’t seem all that out of place to see him banging the skins in some back corner of the U.T. Deke house or squished into that tiny spot on the riser at the Black Cat. Once again, the interest and participation of an older, seasoned musician took Soulhat’s music to a new level.

In those early days, Frosty manned only percussion, backing Ian on the trap. This rhythm-fueled lineup is reflected on the independently released Live at the Black Cat Lounge (Currant Records), a live-to-two-track cassette released to celebrate Soulhat’s 1st Anniversary in the fall of ’91. That tape is long out of print.

In those early days, Frosty manned only percussion, backing Ian on the trap. This rhythm-fueled lineup is reflected on the independently released Live at the Black Cat Lounge (Currant Records), a live-to-two-track cassette released to celebrate Soulhat’s 1st Anniversary in the fall of ’91. That tape is long out of print.

Around this time, other local acts (in particular Little Sister and Joe Rockhead) frequently opened or shared the stage with Soulhat in a supergroup known as Little Joe Soul. The band jammed for hours on end, using different instrumental configurations for different songs (something like the current P-Funk All Stars), grooving on favorites like “Everybody Got Da Funk” [on Little Sister’s Freedom Child LP] and “Love Me Now” [on Soulhat’s Live at the Black Cat cassette] to covers of songs by Buddy Holly and David Crosby.

Sometimes the supergroup played the Black Cat Lounge. Other times, they opened up the expanses of Liberty Lunch, allowing everyone to come in, stretch out, and dance. It was a scene unlike any in recent Austin memory, and I think most of the folks who were there thought Soulhat was destined to be as big as Austin music gets – certainly at the cusp of local greatness.

Much of Soulhat’s early material came from McKinney’s infamous home tapes, which he laid down in his summer ’90 term at S.U..

That summer, it wasn’t uncommon to see Kevin sitting on a brick in his room, mixing tracks and drinking beers. “Garbage Man” [one of several Soulhat songs about working, this one is based on Kevin’s real-life experience as a physical plant worker at S.U.], “Over Easy,” “Captain Funk,” “Mailbox,” “Fleas,” and many others that made it into the lasting rotation, came from those laid-back sessions.

What really made these recordings special (aside from the great music, of course) was the fact that Kevin let nearly anyone contribute to the process. Whether one’s major talent was belching (“Burp for Me Janet”), talk-sung, freak poetry (Matt Johnson’s “I Love Your Guts”), or even if they just owned equipment (Kevin borrowed an old Casio keyboard from this author to complete a few tracks), there always seemed to be a role in the madness for another bored student.

Listening back on these slices of music is like stepping into a time capsule for anybody who had to spend some time in Georgetown during the summer of 1990 (there really weren’t that many of them). And though these 50-odd songs were never available commercially, segments of the tapes have been circulating for years and are well worth looking out for on the shelves of those older Soulhat fans.

But … back to the music. Again, no one said it better than the Austin Chronicle, when it came to describing this music that made people listen when it said in 1991 that “the music itself veers from something approaching funk to strummed folk-rock to blues and out into a ragged improvisational psychedelic fusion.” Indeed, Soulhat took everything good about jamming and melded it seamlessly with tight grooves, innovative songwriting (not exactly “retro,” as it was referred to by many), great lyrics, and those catchy riffs that burned themselves into our collective conscience. It was, simply put, no boundaries approach to songwriting and live performance and it would earn Soulhat attention not only in Austin but soon, around the country.

As the band’s following started to grow, change ensued. Ian left the group in late 1991, and Frosty took over full-time as the band’s drummer. Soulhat began to tour Texas by late ’91, performing gigs in most of the major cities and a few of the smaller ones as well.

As the band’s following started to grow, change ensued. Ian left the group in late 1991, and Frosty took over full-time as the band’s drummer. Soulhat began to tour Texas by late ’91, performing gigs in most of the major cities and a few of the smaller ones as well.

Yet to a large degree, Soulhat still hadn’t earned the respect of the hometown’s musical establishment. Their fans may have considered them to be seasoned live performers after only 16 months of regular gigs, but Soulhat still resembled an Austin outsider. The band wasn’t accepted to the SXSW Musical Conference in 1991 and didn’t even bother applying for a spot in 1992.

Despite the 1991 snub by SXSW, and perhaps in a sign of times to come, Soulhat managed to play to huge crowds that particular weekend (and on 6th Street, no less). Of this, Kevin told the Austin American-Statesman, “When we entered last year and didn’t get in, we just played the Black Cat and that worked out great.” Bill added, “Instead of playing 45 minutes in the Austin area [a reference to the length of the time spot each SXSW act is given], we could choose to play for six hours in the Austin area” (2/27/92). Not bad for a band that still wasn’t considered good enough to be accepted into Austin’s premiere record deal-making machine.

This lone wolf attitude penetrated Soulhat to its core. Independence wasn’t just a badge they wore – it was how the band operated, and how it thrived. With no major label backing them, no status with the media, and no booking agent or publicist, they managed to make their own compact disc (and this was in a day when you couldn’t duplicate a hundred CDs for a hundred bucks). That release, Outdebox, was jointly released by Soulhat’s own record company (Currant Records) and national distributor, Spindletop. The CD, featuring cover art by Austinite Adam Bork (a.k.a. Earthpig), was an instant success locally and quickly became a tangible testament to the vision they’d created for themselves.

True to form, Outdebox highlighted a number of Soulhat’s concert staples, including a live, in-studio 11-minute version of one of their hottest numbers, “Stink Pot”. Avoiding hippie rock clichés, Soulhat eschewed splashy, overdone production and (with the above-noted exception) long, drawn-out numbers, instead opting for clean, short versions of the songs many of us already knew by heart. For flavor, they added guests Jon Blondell on trombone and Danny Levin on cello to a couple of the tunes.

In the two years following the release of Outdebox, Soulhat’s world rapidly began to grow. They toured with Blues Traveler on the west coast and as a result of their strength, also opened a series of H.O.R.D.E. shows. Soulhat also toured the southeast, mid-Atlantic and northeast with the Dave Matthews Band, even trading-off headlining spots with the now monster act.

By this point, Soulhat was finally being heard and courted by major labels eager to find the next Spin Doctors or Blues Traveler. Not eager to jump on that bandwagon, Soulhat repeatedly shied away from attempts to place their music among the ranks of the pseudo-hippie bands that plagued the first part of this decade. When Tower Records’ zine Pulse outlined “Grateful Dead comparisons” in 1993, Cassis responded dutifully, “I have strong feelings about that. It’s not fair. The mentality and approach may be similar, but the music is worlds apart. We’re not a retro act; we’re creating new music.”

Maybe it was Cassis’ fault, for weaving “Fire on the Mountain” and “Other One” jams into one too many of those early shows (the former even showed up in abbreviated form on Kevin’s early four tracks). Yet while the music owed some tiny debt of gratitude to the improvisational rock of the late sixties, it was the business and fan sides of the band that shared so many crucial similarities to the experience of the Grateful Dead. Just as Jerry Garcia had described the Dead’s slow rise to popularity (“we’ve been falling uphill for thirty years”), Soulhat’s rise to fame was on the backs of live music fans (people who had been initiated at live shows, not through studio albums). Early news spread by word of mouth (since the Black Cat did not/does not advertise), and the only way you could “get it,” was to go to a show yourself.

Maybe it was Cassis’ fault, for weaving “Fire on the Mountain” and “Other One” jams into one too many of those early shows (the former even showed up in abbreviated form on Kevin’s early four tracks). Yet while the music owed some tiny debt of gratitude to the improvisational rock of the late sixties, it was the business and fan sides of the band that shared so many crucial similarities to the experience of the Grateful Dead. Just as Jerry Garcia had described the Dead’s slow rise to popularity (“we’ve been falling uphill for thirty years”), Soulhat’s rise to fame was on the backs of live music fans (people who had been initiated at live shows, not through studio albums). Early news spread by word of mouth (since the Black Cat did not/does not advertise), and the only way you could “get it,” was to go to a show yourself.

In addition, Soulhat consistently balked at the system, moving on a slow but steady path toward recognition on their terms. Of this approach, Cassis told The Houston Post in 1993, “It doesn’t make sense to shift our focus to making records with a major label. In this way [making their own records], it’s still on our own terms, but if we mess up, the risks are a little less,” (01/03). Certainly, this opinion reflected Cassis’ own background studying music business, as well as the band’s desire to move forward in their own time, playing by their rules. In terms of integrity, Soulhat was the closest thing Austin had to a Fugazi, and eventually, their adopted hometown would come to consider how lucky it was to have them.

In 1994, Soulhat was finally voted Best Band at the Austin Music Awards. That same year, after securing a contract that gave them an almost-never-seen level of creative freedom, Soulhat signed with Epic/Sony Records. Epic/Sony re-released Outdebox, while everyone waited for the follow-up.

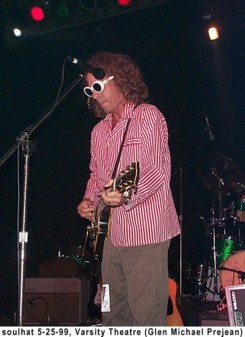

Once out, Soulhat toured nationally in support of their major label debut, Good to Be Gone. Yet whereas Outdebox showcased Soulhat’s trademark grooves and wide variety of influences, the second LP focused strongly on the hard-edged sound that came with a major change in the band’s arrangement – McKinney’s switch from the acoustic guitar to the electric. For although Kevin had occasionally switched to electric guitar for songs like “Love Me Now” during live performances, it had to this point been a relative rarity. Good to Be Gone really began to solidify McKinney’s proclivity for lead guitar work, and really changed the way the band interacted onstage.

Once out, Soulhat toured nationally in support of their major label debut, Good to Be Gone. Yet whereas Outdebox showcased Soulhat’s trademark grooves and wide variety of influences, the second LP focused strongly on the hard-edged sound that came with a major change in the band’s arrangement – McKinney’s switch from the acoustic guitar to the electric. For although Kevin had occasionally switched to electric guitar for songs like “Love Me Now” during live performances, it had to this point been a relative rarity. Good to Be Gone really began to solidify McKinney’s proclivity for lead guitar work, and really changed the way the band interacted onstage.

Kevin’s knack for melody complimented Bill’s heavy blues training in a way that most folks might not have expected. In the same way that twin leads worked for groups like the Allman Brothers Band and Spinal Tap, the addition of a second electric guitar meant heavier, longer jams and, frankly, more possibility. This note was already clear to longtime Soulhat fans, who cherished the two (or so) live numbers that forced Kevin to switch guitars near the end of every night. But one can also hear their wicked trade-offs on lead guitar during the closing section of music that follows “15 More Miles” on the Good to Be Gone CD.

In a sign of some good faith, Epic Records also put some administrative muscle behind the second album’s production. They assigned Brendan O’Brien (producer of Pearl Jam, Aerosmith, Red Hot Chili Peppers, et al) as executive producer for the project. Industry legends like Bob Ludwig were called-in to complete post-production and mastering. The result was, by anyone’s standards, an impeccable accomplishment: a sophomore effort that actually surpassed the initial one in both style and substance. Indeed, Good to Be Gone charted a much lusher musical course for Soulhat, rather juxtaposed to the comparatively subtle forms of the past. Yet the release did seem to confuse fans of the band, some of whom inevitably ran screaming from the quickly-emerging, heavy electric onslaught.

Yet to go out on a limb here, Good to Be Gone was not a change of extreme proportions. Fans who saw Soulhat live were already aware that the jams were becoming harder, even if only at points. One newer tune, “Goldmine,” seemed like a pretty standard pop song. But the live performances came complete with a jam in the middle that could often run fifteen minutes or more – sometimes building to a climax of feedback or noise (or occasionally, “Third Stone from the Sun”) before segueing back into the song.

Yet to go out on a limb here, Good to Be Gone was not a change of extreme proportions. Fans who saw Soulhat live were already aware that the jams were becoming harder, even if only at points. One newer tune, “Goldmine,” seemed like a pretty standard pop song. But the live performances came complete with a jam in the middle that could often run fifteen minutes or more – sometimes building to a climax of feedback or noise (or occasionally, “Third Stone from the Sun”) before segueing back into the song.

“Bonecrusher,” another song that only made it onto an album after many healthy workouts at shows, also featured some very heavy guitar. And that song was actually quite popular from the beginning.

But ‘the change’ wasn’t entirely whole. Soulhat continued to do all-acoustic sets, on occasion. And around this time, Epic also half-released a promotional EP, called Too Gone to be Good, which featured all-acoustic arrangements of songs from Good to Be Gone, including two newer gems (“Goldmine” and “For the Drinkers”). For a while, the EP was supposed to be packaged with the Good to Be Gone CD, free of cost. But this plan never came to fruition and the band and Epic regional PR folks ended up giving out most of the EPs while the band was on tour.

It’s hard to say that Soulhat completely abandoned its roots for full-on rock and roll. But with the brilliant luster of the second CD’s “Bonecrusher” single leading the way, Good to Be Gone just gave fans a different reason to appreciate Soulhat.

The Bonecrusher: continues to receive regular airplay in many parts of the country (the most reliable being Johnny Walker’s 5:10-ish p.m. spot on Fridays on KLBJ-FM, 93.7 in Austin), in addition to being included on the soundtrack of a nationally-released NBA Jams videocassette (playing behind images of legendary Rocket center, Hakeem Olajuwon) and the domestic release of the animated film “Tekken.” Walker’s spot should be noted, though, because he always plays the full-length version of “Bonecrusher,” a version that was only made available to radio stations, warts and all (the extended version features more verses and profanity than the album cut). Though Walker has received complaints about the lyrics of the song, he continues to play it every Friday at 5 p.m. to celebrate the start of Austin’s weekend–God bless him.

Heavy touring followed the release of Good to Be Gone. But those many long hours on the road, with only cursory support from Epic, began to take their toll. Finally, in a move that shocked Austin, Frosty left Soulhat in 1995. Within months, the rest of the group had completely disbanded and it would be nearly two years before they took the stage again.

Well, not exactly two years. While the Soulhat moniker sat rusting in the shed, its former members lit up the Austin music scene in various other acts. Brian Walsh started playing with the Billy White Trio. Bill and Frosty joined Papa Mali and The Instigators. Meanwhile, Kevin and skinsman Conrad Choucroun (also the drummer for Banana Blender Surprise) joined up with guitarist/photographer Adam Bork (a.k.a. Earthpig) to form Earthpig & Fire. And in the Summer of 1996 McKinney, Walsh, and Choucroun rolled out SHAT Records, a trio that built its Wednesday night following at Antone’s with an entirely new repertoire, featuring McKinney’s zany lyrics, songs, and brilliant musical hooks.

Then, in December 1996, something magical happened. All of the former members of Soulhat agreed to play two shows at Liberty Lunch. The show was billed as a “reunion,” but after their first song on that cold Friday night, it was apparent that little had changed musically in 16 months. All the playfulness was there; the melodies which lifted and twisted, flowing effortlessly, as if the last Soulhat gig had been played only the night before, in another bar in another town. Only a few days of practice were seemingly all they needed to rekindle the fire only half the young Austin audience had ever seen, in person. But clearly, each musician’s skill had improved significantly, adding new life to Soulhat’s material, and bringing the audience to the edge.

Then, in December 1996, something magical happened. All of the former members of Soulhat agreed to play two shows at Liberty Lunch. The show was billed as a “reunion,” but after their first song on that cold Friday night, it was apparent that little had changed musically in 16 months. All the playfulness was there; the melodies which lifted and twisted, flowing effortlessly, as if the last Soulhat gig had been played only the night before, in another bar in another town. Only a few days of practice were seemingly all they needed to rekindle the fire only half the young Austin audience had ever seen, in person. But clearly, each musician’s skill had improved significantly, adding new life to Soulhat’s material, and bringing the audience to the edge.

After another few months, the band reemerged as a trio with McKinney at the helm. Cassis declined an invitation to play. Soulhat played a regular Tuesday night show at Stubb’s for a month during the Summer of ’96. And they’ve been turning out a few local shows a month ever since; also playing gigs in Dallas, Houston, College Station, Baton Rouge, and maybe soon in a town near you. The band revamped its setlists, bringing out a lot of old tunes like “Mailbox,” “Over Easy,” “My Man Joe,” and a few the younger folks may not even recognize.